How I write - Editing Part 2 - Developing a process

Working out what to do with my editing

This is the third in an occasional series of posts about writing process stuff that has worked for me, and the second in a sub-series about editing. This time I’m talking about how I finally buckled down and brute-forced my way into learning how to edit.

My first post in this series was a cautionary tale about my ‘word compost’ problem and how and why I finally realised I could no longer avoid tackling it.

This post is where I get specific - once I realised I had a problem and my previous attempts at ‘editing’ were not cutting the mustard, I sat down and taught myself to edit, largely by fairly brutal trial and error.

Herein are the tools and methods that I tried, what I learned and what you might like to try yourself. Plus how I actually applied it to the novel which got me a literary agent, currently titled The Burning Line.

So - it’s January of 2021, I’m turning forty later this year and I've decided that I can’t put off learning to edit any longer. I was coming off a massively overlong first draft of a generation ship SF novel. Far, far too long. If my problem was making compost piles of words, this is more like a landfill. Time to figure this out properly.

Fine, I guess I’ll learn to edit

The first thing I did, of course, was to procrastinate for quite a while by doing research. There is no shortage of good books, blog posts, can't-fail-change-your-life-methods out there for editing. I know, because I’ve read a tonne of them. However, there were three resources that really, really affected how I approached my editing.

The first was reading Self-Editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and Dave King. This book was so useful for me because it helped me begin to understand what editing actually is. That may sound a bit silly, but before I read this book, I had this sort of vague, etheareal idea that it was just * waves hands * making things better? But Self-Editing for Fiction Writers is a very comprehensive and structured look at all the components that go into effective editing, starting with simple clarification and refinement of language and working right up to the structure, tension and pacing of your novel. It gives you a mental framework for approaching editing. I could already do some of this, largely learned by intuition, a handful of workshopping terms I’d picked up over the years and a lot of trial and error. But this gave me a much broader sense of what I could do to improve my work. Highly recommended.

The second resource was Holly Lisle’s article about One Pass Manuscript Revision. This was the first thing I read that gave me a sense that a) it would be a lot of work and I’d need to make my peace with that and b) in order to make good decisions about the small things, I needed to understand and elucidate the big things, like theme and arcs and character motivations. I did experiment with this single-pass method, but ultimately it didn’t work for me. But it was a hugely valuable insight into the mechanics of editing anyway.

The third (and possibly most crucial for me, at least) was Rachel Aaron’s Editing for people who hate editing which I read as part of her excellent writing guide 2K to 10K [1]. This book is widely known (and titled) for the speed-writing method that is at the core of the book, but I got just as much from the chapters on editing. In particular, it blew my mind with the staggering notion that you don’t have to edit a book linearly, front-to-back. I know, wild, right?

Also really, really obvious to everyone but me, apparently. I found the suggestion in this blog post/book that you can identify instances of recurring problems, then jump around in your book fixing all of Problem A, then Problem B, then Problem C, to be completely mindblowing. It suddenly moved editing from a huge, insurmountable, amorphous challenge into something I could quantify and plan and track. And boy, when I realised I could put all this shit into a spreadsheet or a kanban board, I went from dreading editing to positively champing at the bit to get started.

Editing The Burning Line

With my research complete, I sat down to take a look at The Burning Line (it was still called Stringers at the time) and figure out how I was going to tackle this edit.

Making a plan

The first thing I did was to write out how I was going to approach my edit - that’s essentially a shorter version of this blog post. I wrote out which stages I was going to do, in what order and which tools I’d use. I recommend doing this for a couple of reasons. Firstly, it gives you a plan to look back on so you can see what your intentions were. Second, it makes it feel like you know what you're doing.

In practice, this plan fell apart almost immediately.

The paper edit

I started by printing out my whole book and then reading the entire thing on paper, while making notes in the margins, trying to rewrite sentences and paragraphs and attempting to note recurring issues in a separate list. This absolutely works for some people, but wow it does not work for me. My handwriting sucks, managing the paper is a pain and even with everything printed out double-spaced there’s not enough space most of the time for the edits and notes I want to make.

I had tried editing on paper before, but without a clear idea of what editing meant. At least this time I was reading with an eye to fixing actual problems, rather than just vaguely striking out the odd word. Still, it really doesn't work for me.

The paperless edit

The next thing I tried was the same idea, but using a PDF with my iPad and an Apple Pencil. I got about fifty pages into doing that before realising that it had most of the same problems for me as the paper edit, but with additional wrinkles caused by working on a smallish screen and having to zoom in and out to write notes. It might save a couple of trees, but it wasn’t getting me to the edit any quicker.

Readthrough and task list

Once I’d finished my paper markup, I then realised I had a huge list of uncategorised things to be done, spread across multiple sources of information, including my marked-up paper manuscript, my notebook, my iPad and the original Scrivener file.

Some of these things were single words that needed to be cut or changed. Others were huge, multi-instance continuity errors that would require ripping out whole chapters and heavily rewriting others. But I had no way to tell which was which.

So I created a task list.

I started by building a couple of massively overly-complicated kanban boards in Notion, attempting to map recurring issues and statuses into nice neat columns. Notion is a very powerful and pretty database tool, but it can almost be overwhelming in its options. So in the end, I reverted to what I knew - spreadsheets.

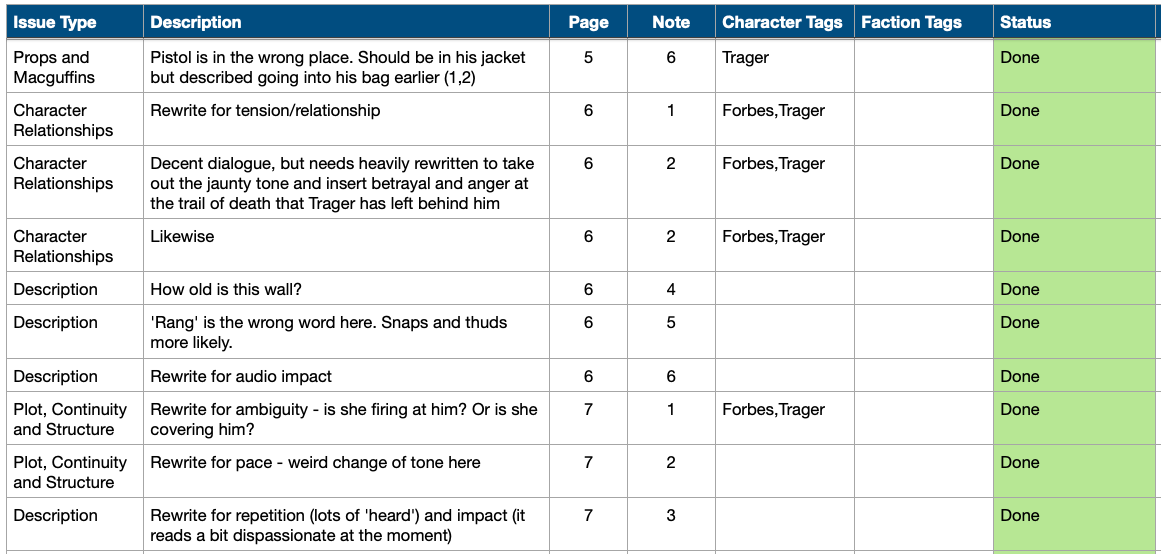

The task list I ended up actually using was structurally relatively simple, allowing me to note page numbers, the status of the task, a category, a sub-category and so on. I had a whole taxonomy of different types of edits. It was… a lot. Here’s a fairly typical chunk:

So in the end I had a fairly complex multi-step process. It was detailed and exhaustive and it got me through that first big structural rewrite pretty effectively, but wow it was a lot of work.

I also couldn’t shake the feeling that some of these steps were unnecessary for me. When I found myself scribbling a rephrased sentence or a note about ‘adding more explosions’ to my paper or PDF manuscripts, then typing that into a spreadsheet so I could categorise it, then, finally, actually making the change days or weeks later, I began to wonder whether it wouldn’t be easier to somehow skip straight to the ‘make the changes’ part.

However, I already knew that I couldn’t just open my Scrivener file and start editing, at least not when I’m trying to actually read the book as a whole entity. Something about reading my own words in a text editor window makes it really difficult for me to view them even semi-objectively, so I end up reverting to skim-reading, typo-hunting and generally not actually editing.

A breakthrough - Ebook markup

Much later on, during my fifth or sixth run-through of the book, this time tackling things my beta readers had brought up, I hit on the idea of using the built-in commenting feature of my ebook reader. I had been a Kindle user for many years, but in 2021 I finally got a Kobo Libra H20 (sidenote: this is a phenomenal ereader - the current version is the Libra 2). The Libra has an operating system based on Linux and it's quite easy to modify the software. I discovered there was a very simple change [2] that would allow me to quickly export text files with all of the highlights and annotations from a given ebook.

Aha! I thought. What if I just read the book and made notes on it with my eReader, then exported those and worked straight off the list of comments!

This turned out to be exactly what I needed and this simple two-step process has become the foundation for my new approach to editing.

The beginnings of a process

In the book I'm currently writing, I’m experimenting with a new ‘edit-as-I-go’ approach which is a little different to this. But for the last three or four full edits I did on The Burning Line, this was the approach that I took:

- I use Scrivener to compile an ePub, which I then used Calibre to sync to an ‘Editing Drafts' folder on my Kobo eReader.

- I read the book as a normal reader would. Something about my eReader gives me just enough distance from the text that it feels like reading something that someone else wrote.

- As I read, I highlight text and write (very) short comments, usually 3 or 4 letter acronyms. eReaders are amazing, but typing on an e-ink keyboard still kind of sucks. Here’s a few of the acronyms I use:

- RFRS - Rephrase

- CONT - Continuity issue

- ANAC - An anachronism - something that sticks out as being wrong for the setting

- ENV - Add more additional environmental detail

- UGH - Terrible dialogue, clunky exposition, just something that needs looking at

- RCR1 - For ‘recurring issue 1’ and so on [3]

- Once I'm done reading, I export the text file from my Kobo with all the issues, then Ctrl F my way through the text file, fixing every instance in the draft. This is amazing - I can quickly scan through and fix all my RCRs, or all of my continuity fixes, or all of my ‘ugh’ dialogue, just by searching a single text file. Text files are hugely underrated as tools for managing and searching data [4].

- Once all the recurring issues are done, I go through and fix all the one-offs.

- As I complete each issue, I either put a large X next to it in the text file, or I just delete the line if I'm feeling feisty.

- Re-export, re-read, repeat until I’m screaming and can’t bear the sight of the book.

That’s the foundation of my editing process now, the one-two punch of Kobo and Scrivener, working together to both give me the tiny bit of distance from my own work that I need to read it somewhat objectively, as well as the speed and flexibility to actually get in there and make the changes.

As with my writing routine, I've learned over time that if I want to do something, the key for me is to focus on simplicity and repeatability. While graphs and spreadsheets are nice, simple lists and the power of search works so much better for me, as well as taking a lot less time and effort.

So there you have it - that’s how I edited The Burning Line perhaps twelve or thirteen times over the course of a year.

In the next post, I will explore a crucial refinement that I’m making to my editing process now, as I write my next novel. Because if I can avoid it, I’d rather not edit the next one fourteen times over. The Burning Line had a lot of problems, so multiple passes were required to iron them all out. My hope is that this new writing/editing model will mean I get to a much cleaner draft, much earlier in the process.

You can read all of that in the next part:

Editing Part 3 - How I actually do it.

You should buy this book - it is hugely motivating and thoughtful and got me pumped for writing after a long fallow period. The claims Aaron makes about word counts can seem a bit wild, but her combination of outlining, clearly understanding your own story, making time for writing and the (revelatory, to me) practice of non-linear editing really got me excited for writing again. Also it's short, you can read and re-read it quite quickly when your enthusiasm flags in the middle of a long draft or edit! I know I have. ↩︎

I used the second set of instructions on that page, which spits out a nice little text file. Apparently on long annotations they can sometimes be truncated, but since most of my annotations were a word or two long at most, it wasn't an issue for me. And having a text file I can search through and edit directly was much more important. ↩︎

This was an innovation I came up with naturally myself and it has been very, very useful - it lets me create strings of related issues (such as changing references to an event in a character’s past throughout the book) as I need them, on the fly. The first time I add an RCR, I’ll type a brief description of the problem (i.e. ‘RCR41 - Make this guy Australian’). Then every subsequent incidence I can just use the acronym. When it comes time to actually make the guy Australian at every point in the book where his nationality is mentioned, I just search for RCR41, then step through my annotations, using the text snippets I highlighted to find the corresponding chunk of text in Scrivener. ↩︎

This works so well because when you highlight text in Kobo it gets exported along with your comment. That means you get a little snippet of text you can plug into Scrivener to find the passage. This is especially helpful because things like page numbers change every time you compile from Scrivener, so in a long, structural edit, you might be trying to find a passage from your paper copy or your spreadsheet which has moved by 100 pages. Scrivener's search feature is fast and incredibly flexible, so it makes finding stuff based on these little Kobo snippets very easy. ↩︎